Words of Hope, Words of Life.

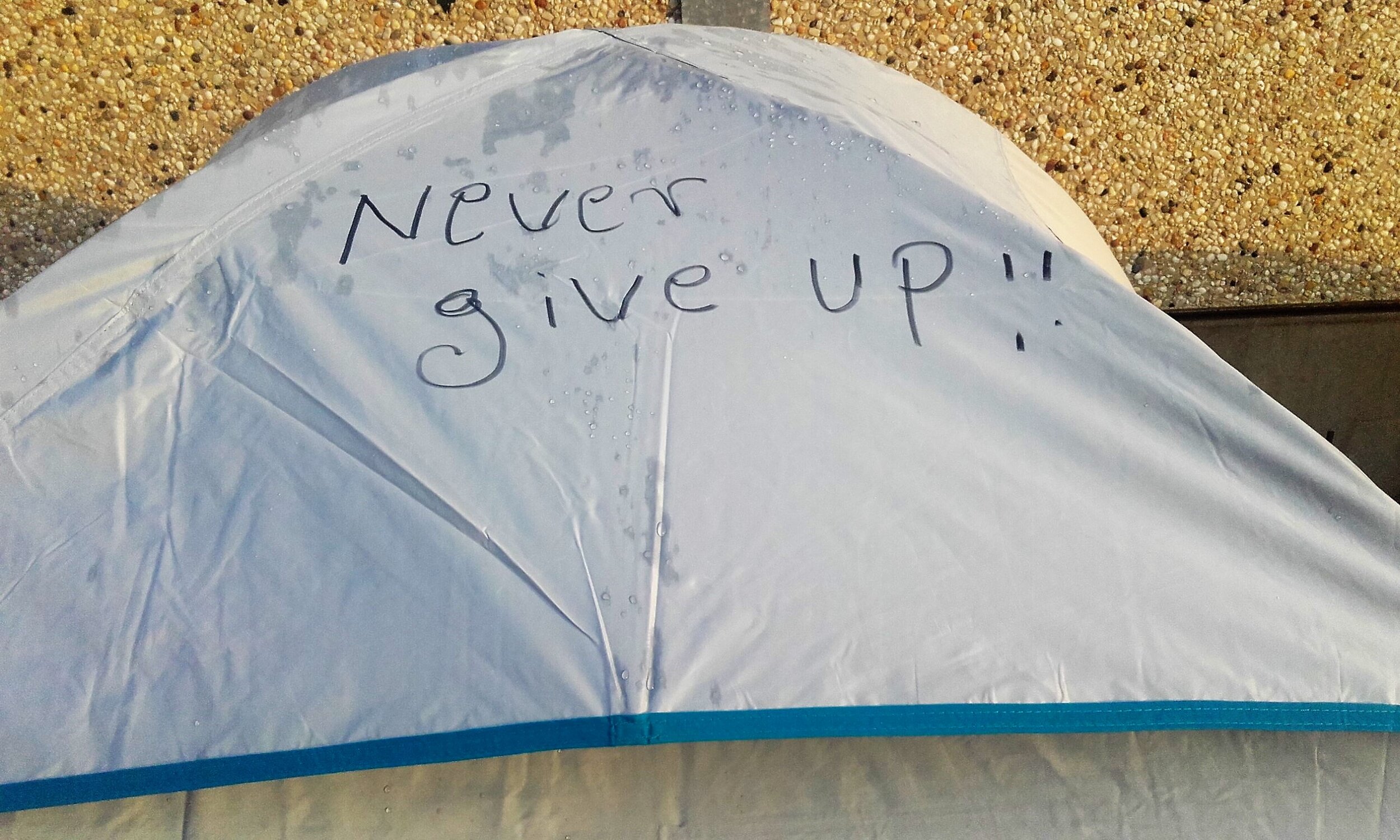

Anzio, the wordsmith. His broad smile and the laugh lines around his eyes communicate joy. He’s part of the cooking team that’s come to Maria Skobtsova house to prepare a celebratory feast for Orthodox Christmas on January 7th. Seeing the white board on the wall, he asks for a pen. ‘Life is…’ He stops writing. ‘How do you spell ‘sacred’?’ I tell him. ‘Life is sacred’; his triune is complete. Merhawi now takes the pen; ‘I didn’t decide to be born’, he writes, ‘I won’t decide when I’ll die; just let me live how I want’. His smile is one of satisfaction, yet hints at something deeper, more painful. Back in the Eritrean camp, Anzio has been at work on the tents that line the base of the UK funded ‘security wall’. ‘Dear problems please give me some discount, I am your regular customer’ is penned across the flysheet of one of the tents. On his own, he has written ‘Never Give Up !!’. But this has irked the CRS, the French riot police. ‘They came and cut it’. Duct tape covers the slash, near obliterating the ‘N’ of ‘Never’.

A map of the world crisscrossed by planes and flight lines adorns Yoel’s small rucksack. An open world, travel friendly. But what irony. Yoel, like most of the Eritrean refugee community in Calais, has crossed the world as a commodity; he’s been trafficked, tortured, and, once in Europe, rejected by the asylum system. His only hope now is to stow away in a UK-bound truck. But these are changed days; Brexit has happened. ‘Where are the trucks?’ the guys ask daily. It’s well into January. The flow of trucks arriving into France from the UK continues unabated. But nothing is going the other way. ‘Is UK closed?’ I offer words that I hope will reassure, that more than half of the UK’s imports come from Europe, the trucks will resume.

Fireside. An architecture of timber, shaped like a mini-Stonehenge, surrounds the fire. After endless days of rain, the logs must first be dried before being put on the fire. Johnathon, chef supremo, is whittling an old broom handle. It will be his pot stirrer. The words on his t-shirt include ‘Never be unwilling to do a good deed’. ‘You want tea, coffee, milk?’ Seeing the ‘Max’ logo across dozens of half litre cartons of milk, I realise supplies are good. I opt for milk. The Max carton stack offers a clean haven for ‘CRS’, the camp cat, who appears used to a more salubrious setting. She pads delicately across the muddy terrain. Ultra-biddable, she’s scooped up and held close to a chest, yanked into someone’s arms by the tail, sleeps the night in the shelter of a tent. But she’s no ratter. Rats run amok, eating the food, gnawing holes in the tents. They play brazen games of chase on the perimeter of the camp. CRS ignores them. But the real CRS, the Compagnies républicaines de sécurité, ignores nothing. Aklilu the dancer, Aklilu whose scarred adult face lights up with the cheekiness of a little boy, is nursing a broken right wrist. The plaster cast, not yet twenty four hours old, is already staining brown. ‘CRS, they hit me’. His vulnerability is raw. He’s a little boy again. Someone puts music on. His face lights up. Soon he’s swinging his good arm to the rhythm of the sound.

‘I need to go to England. Can you help or catholic church England?’

‘There is nothing I can do, Negassi, and there’s nothing the church can do. I am sad to tell you this.’

There comes a typically gracious reply; ‘Thanks very much, Alex. I am sorry, no sad please’

The next request is manageable. I’m approached by another Eritrean as I’m leaving the swampland of the largest of the Eritrean camps. ‘Can you take a bible to UK?’ Several days pass and several people have been involved before I’m handed the bible wrapped in two sleeping bag covers. In London I hand the bible to Teodros. His gratitude is boundless. I’d been expecting a young Eritrean; Teodros’ hair and moustache are liberally peppered with grey, his hairline receding. He has a gentle, warm face. ‘Thank you, thank you,’ His gratitude is boundless. ‘I am happy to meet you, and my bible. This book’, he pauses, looking at me intently, ‘this book is my life’.

Alex Holmes January 2021