“An Architecture of Care in Calais”

by Amy Frikholm

Copyright © 2024 by the Christian Century. Reprinted by permission from the January 2024 issue of the Christian Century. www.christiancentury.org

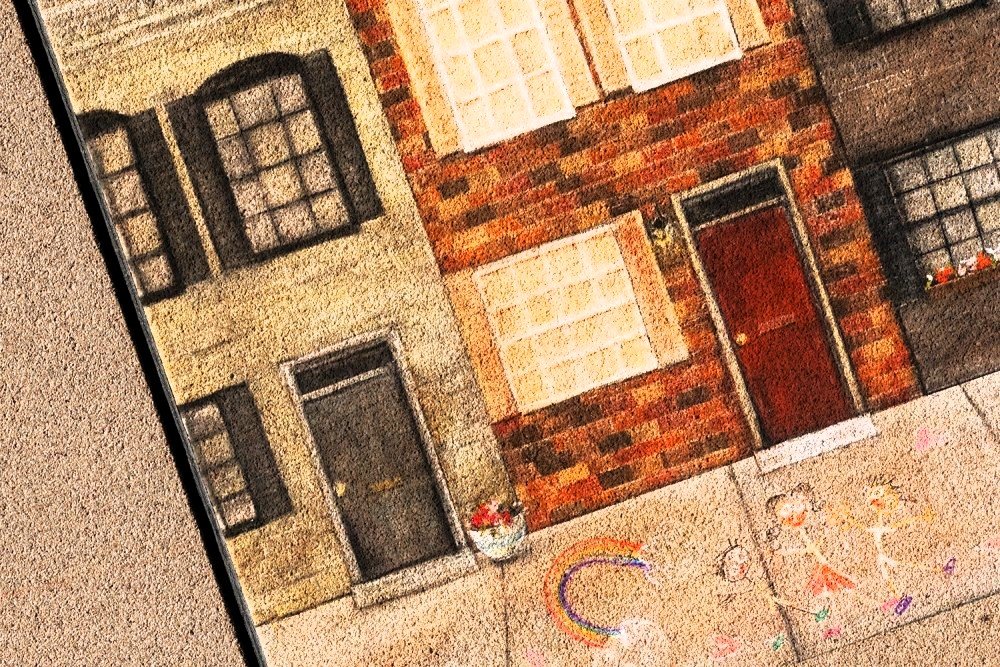

Illustration by Elizabeth Niemczyk

“Never underestimate the power of the house,” reads a small sign hanging on the wall of the Maria Skobtsova House in Calais, a port city in northern France.

The house in question is a row house in a middle-class neighborhood with partially trimmed hedges and rose bushes. The only thing that sets this house apart from every other house on the block is a simple sign taped to the window that says, “Maria Skobtsova Refugee House.”

On the day in June when I arrived, the front windows were wide open to catch a breeze. Ieva, a young Latvian woman and frequent volunteer, opened the door for me. We’d arranged to meet at 9:30 and maybe have prayer.

Maybe is a key word at the Maria Skobtsova House. Maybe we will have prayer. Maybe this is a day when no new refugees will come. Maybe several new families will arrive. Maybe everyone came in very late last night and will be sleeping this morning. Maybe the weather is good, and tonight refugees will try to reach the United Kingdom by crossing the English Channel in small boats. Maybe the weather is bad, and today is just a day for waiting. Maybe, as on this particular day, little Maryam will already be awake and toddling around, and prayer won’t be quite as attractive as following her and trying to entice her to the table to eat something. (Names have been changed to protect those still in the process of seeking asylum.)

Maryam’s mother, Layla, was at the stove in the tiny kitchen making Iranian-style scrambled eggs in tomato sauce. Ieva put on a pot of coffee. Asma, a Syrian woman also staying in the house, said no to eggs because she was fasting on the eve of Eid al-Adha. We used Google Translate to look up the word that Asma wanted to say about her intentions: “Forgiveness.”

The motion of the house can go from frantic to still, as if it were a little boat on the ocean subject to winds that no one can see or control. Ordinary moments are interspersed with moments of intensity. Full stop; frantic motion. The only thing that volunteers are attempting to do is hold the space so that refugees, who are caught in political and social winds, might have a place to be restored. One of the things that providing hospitality means is taking on a refugee’s own rhythm. Some days, Ieva says, are spent just sitting at the wide, wooden table and having coffee, welcoming one person after another, whoever they are, whatever they need. How you welcome one person, Ieva says, is how you welcome every person.

Other days are spent in trauma. In January, an Eritrean woman was separated from her children on the beach. It was dark, the smugglers saw the police coming, and they launched the boat with her children in it but not her. Years earlier, this woman had lost her son when crossing the Sahara desert and had spent seven years searching for him, through every government and international agency, until they were finally reunited. Now this. He and his half-siblings were crossing the Channel without her. She had an emotional and psychological breakdown on the beach. After some time in the hospital, she came to the house to recuperate and figure out what to do next. It is not uncommon for people to arrive at the house wet, injured, exhausted, dirty, and hopeless.

The house’s origins lie in an impromptu camp in Calais that came to be called the Jungle. Calais is the closest potential crossing point to the UK, a destination for many refugees. In 2015, in the midst of one wave of the ongoing worldwide refugee crisis, refugees came to Calais from all over the world but predominantly from the Middle East, Africa, and Afghanistan.

The Jungle, which housed more than 10,000 refugees at its peak, was in one sense just a set of tents and muddy pathways where people who had no other options landed. But it became a place where refugees worked with a wide array of organizations and initiatives to create what researchers Dan Hicks and Sarah Mallet call “an architecture of care and dignity.” People—refugees and sympathetic observers—organized clothing distribution, food distribution, a library, playgrounds, arts and crafts, women’s and children’s centers, chapels, and mosques in the camp.

This is where a Catholic Worker named Patricia McDwyer-Wendzinski, a monk named Brother Johannes, and a Baptist minister named Simon Jones met Eritrean refugees who had set up a small chapel. Through praying with these refugees and discussing the situation in the camp with them, they discerned the need for a house that would be a refuge for the many volunteers working in the camp. They were inspired by the work of 20th-century Orthodox nun and saint Maria Skobtsova, who set up houses for refugees in Paris. Once the house was available, volunteers used it for respite—but soon they started bringing refugees to the house as well. So-and-so had a broken arm. So-and-so was very sick. So-and-so was traveling alone and was unsafe. The house became a refuge for those on this path who were especially vulnerable.

In 2016, the local government bulldozed the camp. Six thousand residents were dispersed to temporary reception centers around France. The remaining people scattered into more makeshift and informal settlements throughout northern France. The mayor of Calais, Natacha Bouchart, has since instituted a policy of no permanence, and she has instructed the police to destroy any camp or settlement they find within three days. She has also repeatedly attempted to ban food and clothing distribution, an act that was struck down by a local judge in the fall of 2022.

Dispersing the camps does nothing to address the real human crisis, but none of the governments experiencing an inflow of refugees has been capable of the kind of long-term thinking that would create an alternative architecture of dignity. Instead governments have been implicated in bolstering the work of smugglers and increasing the misery of refugees. Recently the UK government has tried telling refugees, via a law that took effect in July 2023, that they will not be able to apply for asylum if they come by small boat or by truck. It has floated the idea of sending them all to Rwanda as a “safe third country,” an idea struck down by courts. It tried housing refugees on a barge that quickly became unsanitary and unsafe. These laws and attempts to discourage refugees through what we might call an architecture of suffering have done nothing to stop the flow.

Into the gaps created by governmental failures and criminal gangs working as smugglers have stepped a variety of organizations who work together to create if not a safety net for what is an extremely dangerous and hazardous path, then a kind of patchwork. In Calais, a group called Utopia 56 drives around the city assessing the refugee situation on any given day: the size of the camps, the conditions of the people, any injuries. They assess what kind of needs people in the camp have. They keep an eye out for women and children. When they see specific needs, they might call the Refugee Women’s Centre, which no longer exists as a physical center but has volunteers who drive around in a van, park on the edges of camps, and distribute food, clothing, shoes, outdoor gear, and whatever else they may have.

When they see specific housing needs, they call the volunteers at the Maria Skobtsova House and bring over refugees. The house continues to welcome both refugees and volunteers from all over the world. There is a network of such houses in Calais, small in number, informally organized, and always under the threat of being shut down by a hostile local government.

“Why does everyone want to go to the UK?” I asked three volunteers—Ieva, a Brit named Alex, and Joelle, a French nun—as we sat out on the concrete patio after prayer one morning.

“There isn’t one answer to this question,” Ieva said. For some people, it’s language, culture, a sense of familiarity. For others, relatives live there. Others are fed by rumors that the UK is more receptive to their plight than other European countries. Others have been kicked out of the EU but have nowhere safe to go. For many the UK is the country of last resort.

In the afternoon of the day I spent at the house, a new family arrived with two volunteers from the Refugee Women’s Centre. Wahiba, the mother, broke her foot in one of the trenches dug by French police to keep people from getting to the beach. (The French government has an agreement with the UK government, which pays it for its prevention efforts.) She was determined, however, that the family would cross and soon. In her native Sudan, Wahiba was a human rights lawyer. Her husband, Mustafa, was a political scientist and journalist whose work was primarily focused on Nile Basin food security. His outspokenness made him a target of multiple governments. The family had been on the road for three years.

Their son, Amani, is five and speaks beautiful, clear French. Asim is three and was born in Italy. Little Ayman was born just eight months earlier in France. The parents joked that the day they arrived in Great Britain would be their birthdays, their new wedding anniversary, and the start of an entirely new life. But first they had to get there.

The way that all refugees who end up in Calais do this is by paying smugglers. The house maintains a precarious existence between smugglers and governments. Volunteers have no contact with smugglers and are scrupulous about focusing their efforts on hospitality and the architecture of dignity. They worry constantly that the government will appear with an eviction notice one random day. When a surprise inspector came just two weeks before my visit, he grumbled about the stairs not being wide enough. The threat was clear enough.

All the crossings happen at night. While the French police try to prevent launchings, once the boats are in the water they do not try to stop them or perform rescue operations. It is very dangerous to rescue people who don’t want to be rescued, Ieva told me. According to volunteers, the French coast guard will sometimes even accompany the boats to English waters to ensure their safe crossing.

The little boats that launch from Calais have as many as 60 refugees on them, but the smugglers don’t travel with them to ensure safe passage. Instead they “hire” a refugee to serve as “captain” for the crossing. This person, usually a young man with little or no experience, is given a discount for the crossing and will take the fall if anything goes wrong. This means that the smugglers themselves are protected from the exposure that crossing creates.

The boats’ motors are not equipped to take them all the way across the channel, a distance of about 20 miles. The motors are intended to die in British waters, where the British coast guard will perform a rescue, take the refugees into custody, and process their asylum claims. The British government maintains a daily website that publishes how many people attempted to cross in how many boats and how many “uncontrolled landings” occurred. At present, the British government aims to prevent uncontrolled landings. It prefers to pick up would-be refugees in the water. Some nights the British coast guard apprehends upward of 50 boats, other nights none at all. In August, a boat capsized when its engine failed, and six young Afghan men were killed.

If all of this sounds impossibly dangerous, consider that international law provides for almost no safe routes for an asylum seeker to take. The most straightforward way to receive asylum is to arrive in the country in question and ask.

Wahiba and Mustafa spent the afternoon bathing and feeding their children. They were both exceedingly gentle with these motions, as if life on the road afforded them no irritability. While Asim received his bath, Amani and I played Legos on the floor of the living room that is also a chapel. “Can you build me a machine?” I asked him. He looked skeptical but also intrigued by the idea. He built himself an elaborate machine and me a simpler one.

Rachel and Joseph, two married American Mennonite volunteers, returned with their own children from school, and suddenly there were seven children in the house, all running around. A volunteer played chess with Layla’s son, Yousef, and other boys gathered around to watch. Rachel was the evening’s cook, and “We are having American food!” reverberated around the house. Rachel improvised a vegetarian chili and made “corn bread” out of what appeared to be a large bag of donated semolina.

At dinner, all gathered around, even though Mustafa, like Asma, was fasting for the Eid. In the kitchen, Layla told me that she will never, ever go back to Iran, despite the ten brothers and sisters who live there, the mother who longs for her, and their ancestral land. I didn’t fully understand what was behind this never, but I heard its force. One of the unspoken rules of the house is not to ask for stories that are not offered. Many things happen to force people out of their countries, and many other things happen on the road that add trauma to difficulty and difficulty to trauma.

After dinner was cleaned up, Alex and Amani invented a game where they built a rocket to the moon. “A la lune!” Amani cried as he spun around the house with his rocket. “A la lune!” everyone cried in response.

I left the house as the sun was setting and walked back to my Airbnb nearby. On each of the next five days, the UK website said zero boats and zero people. The wind was gusty across the Channel. Then one day, the website reported three boats, 155 people. There was no way for me to know if Mustafa and Wahiba, Layla, Yousef, Maryam, and Asma were among them.

Meanwhile, the house on the edge of France continues on. People come and they go. Volunteers and refugees alike arrive, make coffee, play chess and Legos, pray, wait, try to imagine the unimaginable and control the uncontrollable; they plant seeds in containers on the patio or water those seeds that they likely won’t be around to see flower or fruit.

Those searching for viable, humane alternatives to today’s architecture of suffering propose several things that might allow people to claim asylum without having to take harrowing journeys. Could there be a global humanitarian asylum visa system, accessible beyond the borders of the countries where refugees believe they will be safe and have their best chance to survive and thrive? Could there be ways to create migration pathways that include community sponsorship, employment and education opportunities, and family reunion centers? Given all the money that governments pour into failed prevention and the architecture of suffering, and given the fact that these efforts have done little but bolster smugglers and traffickers, might they instead pour these resources into creating legal aid and humane conditions? As long as the answer to these questions is still no, as long as those lacking humane imaginations still dominate governments, places like the Maria Skobtsova House provide vital links.

Philosopher Donna Haraway has proposed calling the current age the Chthulucene, taken from the Greek word chthonos, meaning “of the earth.” The Chthulucene, she says, is a time full of refugees—humans, animals, and plants. Living well in this era means participating in the reconstitution of refuges, places where these many refugees can find safety, rest, and peace. If global solutions to the massive global refugee crisis evade every world government, if safe routes are still too utopian an idea, these refuges will be needed. Look for a little sign in the window, on an ordinary street, next to a rosebush, where the door is open and the coffee is on.

Amy Frykholm. The Century senior editor is the author of five books, including Wild Woman: A Footnote, the Desert, and my Quest for an Elusive Saint.